Over the years we’ve had a number of people share their OVERLOAD experience. We want to thank Owen Drolet for sharing his.

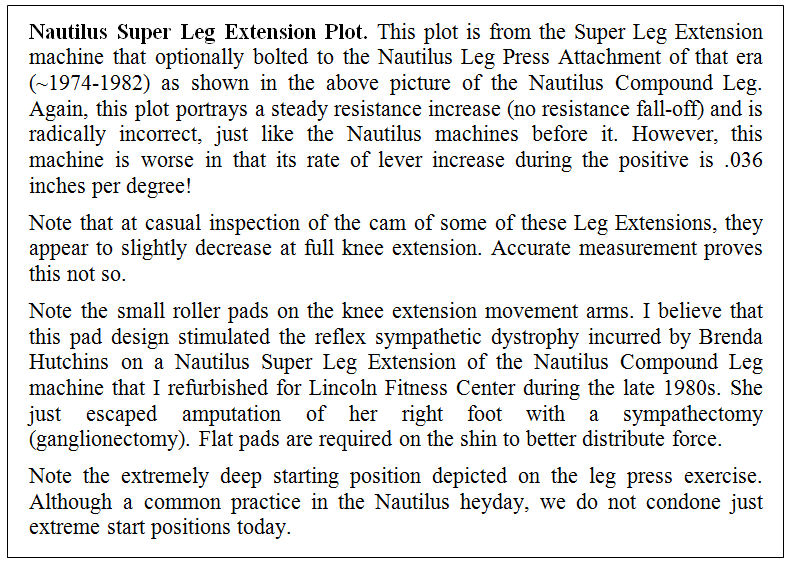

Having been unable to attend The Future of Exercise conference last fall, my wife Roxanne and I were determined to visit Overload as soon as we could in order to try the various TSC machines as well as the rest of the dynamic line. But, having recently opened our own facility, The Strongworks, in West Hartford, CT, we were too busy building the business to come up with a serious plan and time flew by. Then I purchased the DVDs of the conference when they came out in March, watched them all immediately and decided the presentation by Gus was where my wife should start (while my business partner, she is not involved in any of the training and a lot less obsessed about all this stuff than me). As soon as it was over, she turned to me and said, “Get in touch with Josh, we need to get out there sooner rather than later.” So, I let Josh know what we were looking to get out of a visit, settled on a price for what they would be providing, and before we knew it we were on our way to Cleveland.

One of our main goals was to experience as many of the feedback systems as possible, both dynamic and static, with the potential plan of purchasing either the iPOPD or the iMulti to augment our current machines and, more crucially, to use as a teaching tool for our clientele and in our own training. But we also wanted to experience what a first time Overload client would encounter during an initial consult.

We arrived at Overload at 7am on a Wednesday, and were soon in an office with Josh, going over what a new client would hear, starting with the Preliminary Considerations for Exercise. As he went through the list he would stop occasionally and come out of character, as it were, to speak to us instructor to instructor, explaining the underlying logic and timing of the information conveyed. (It was then that he would typically stop to eat some of the raw oysters he had brought along for breakfast – I’m guessing real first time clients don’t get to see that…) It was a really useful demo and I was glad to see it closely mirrored what I tell my new clients. Next we went off to begin a slightly modified initial consultation-style workout, with Roxanne being put through the paces first. We chose to do it this way partly so I could observe Josh’s instruction while I was still fresh, and to spare my ego – Josh pointed out that when he had done this with couples in the past, the woman typically performed better. Having trained my wife for a long time, I didn’t doubt him. We were both a bit nervous, not unlike Dr. McGuff, who described his apprehension before working out with, as he put it, “such well-known Form-Nazis” – fortunately we wouldn’t be doing it in a crowded ballroom like poor Doug.

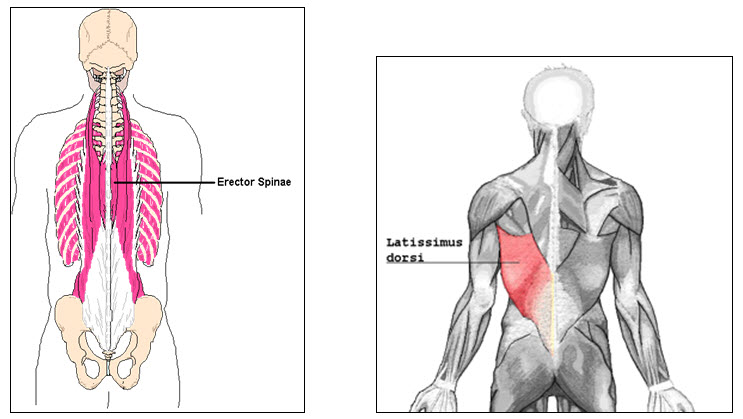

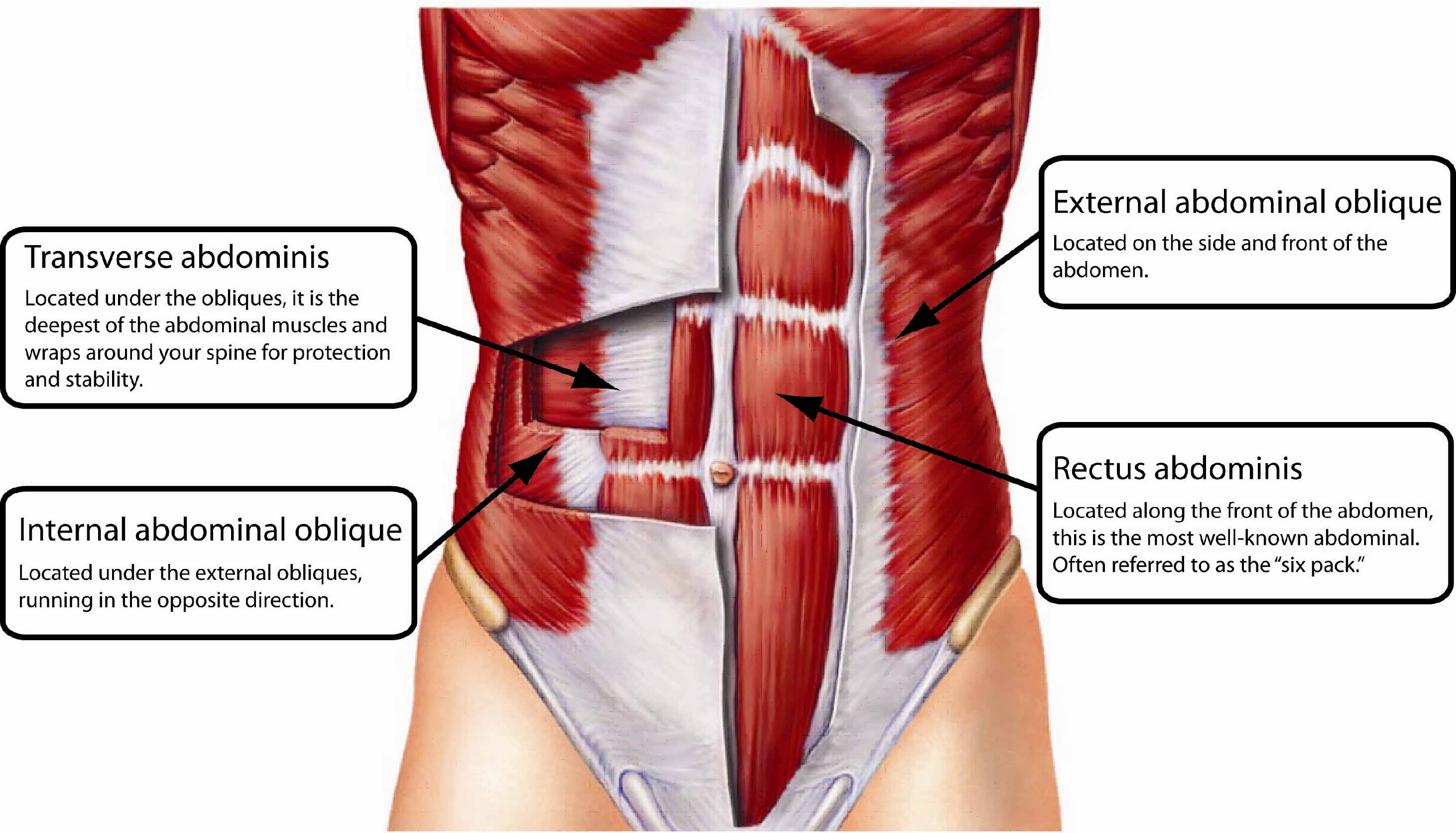

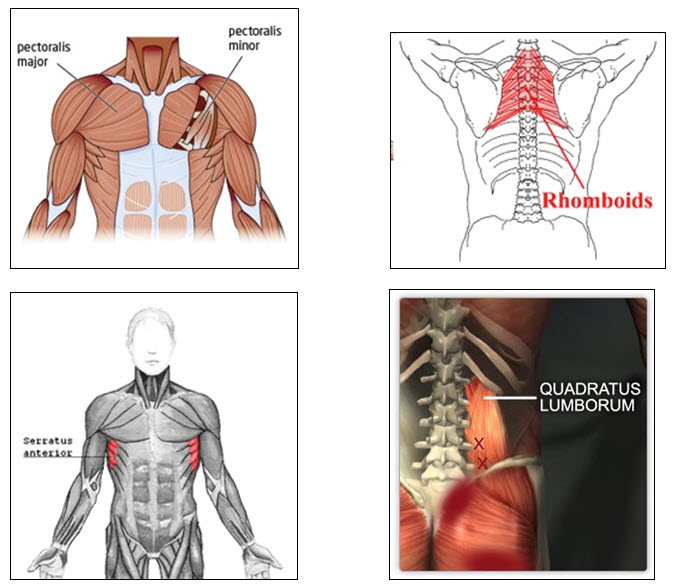

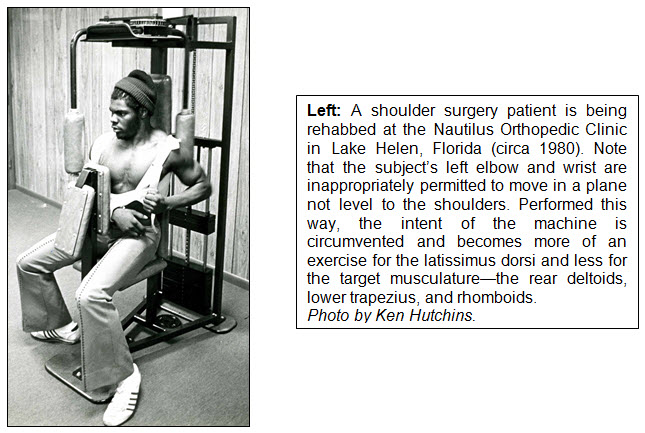

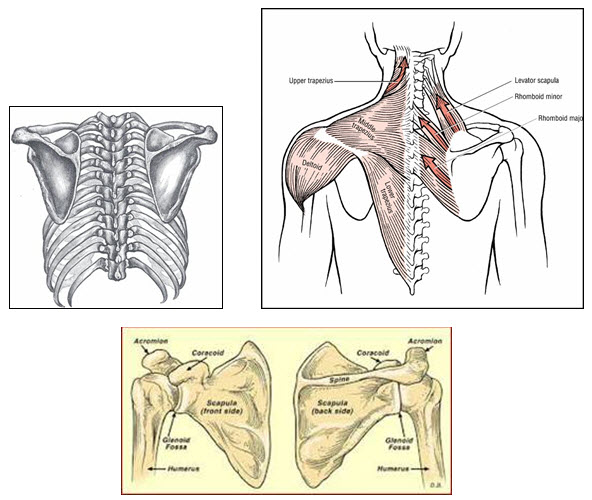

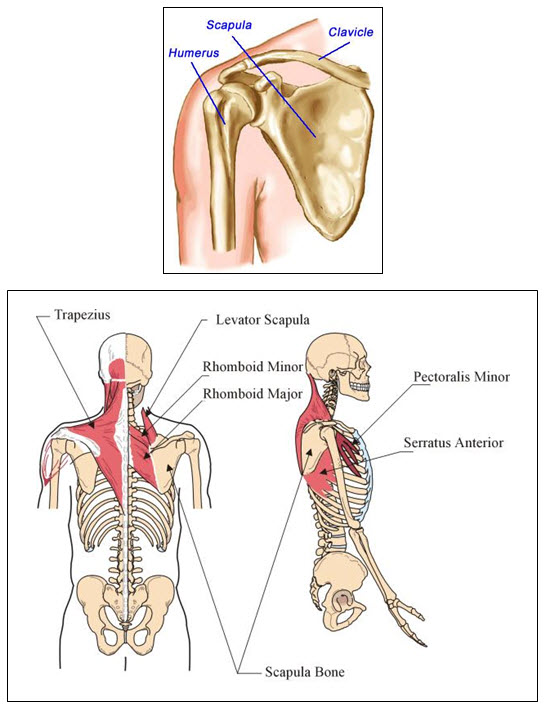

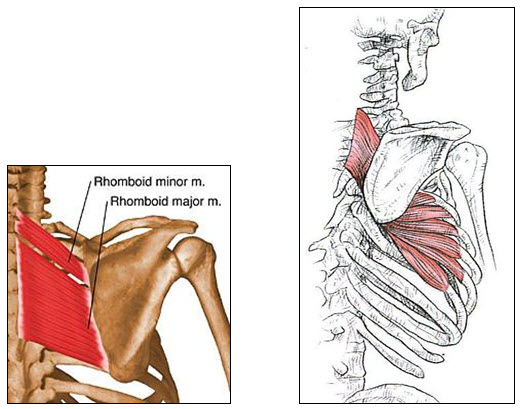

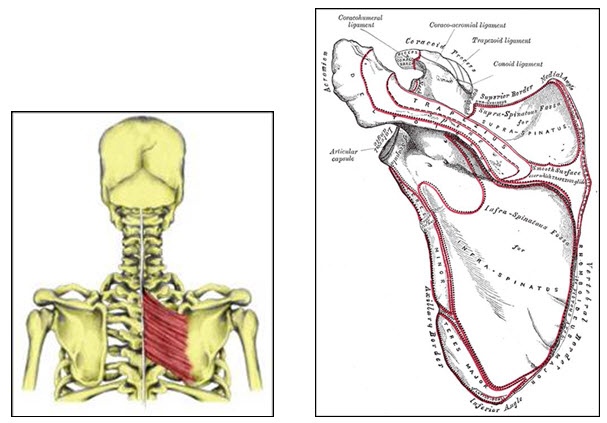

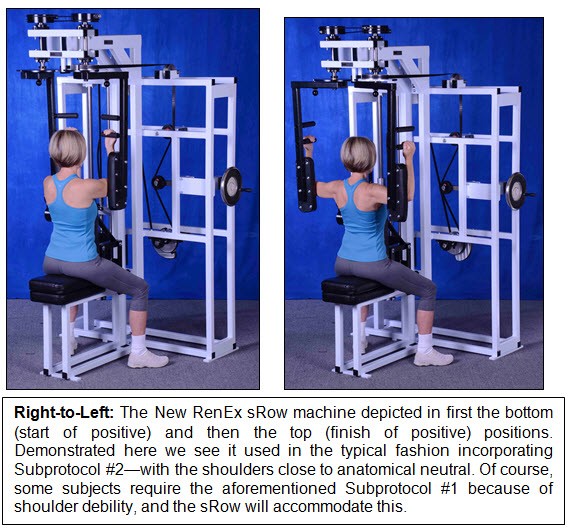

First up was the leg press with feedback. After getting Roxanne fitted and set, Josh instructed her to build up force such that the line produced on the graph moved upwards at a 45-degree angle. Once her force matched that of the weight stack, movement would commence. I’m proud to say that she nailed the build up, producing a perfectly angled line. She then put in a solid performance following Josh’s commands and he eventually terminated the exercise because he had underestimated her strength and didn’t want her lingering there forever. She then moved to the overhead press and though Josh pinned more weight than he had originally planned based on her leg press display, and while she did ultimately even reach failure, it was after a very long set. From there she moved to the simple row and Josh had to make yet another adjustment to the weight selection after she began, but this time in the other direction. While much stronger than the generic starting weight used for a typical first-time female client in the first two exercises, in this area she was noticeably weaker than average. This speaks to how important that machine may be to service an often overlooked and incredibly important part of the back musculature.

It was now my turn to go through the initial leg press routine, with Al Coleman overseeing my workout. Wanting to make sure I didn’t build too quickly, I ultimately built the force much too slowly, taking, I believe, upwards of 30 seconds to move the weight stack. By the time I had started the actual movement I was already feeling significant fatigue. The importance of gradualness, which the RenEx guys talk about all the time, suddenly had a new meaning no amount of verbiage could have conveyed. As the exercise progressed, the feedback was both fascinating and disheartening as I could see myself unload, however slightly, on the bottom turnarounds, though it was immediately clear that such discrepancies could be fixed in time, now that I could see what I evidently wasn’t feeling. While the weight was a bit light for me and I went well over four minutes, I did eventually reach failure when trying to come out of a bottom turn. Interestingly, in hindsight, I can tell you that failure on the RenEx leg press felt much closer to the diminishing force capacity you see and feel on a static machine with feedback then it does on any other leg press I’ve tried, which always feels as much mechanical as muscular.

I then did a set on the Ventral Torso, which had been at my request. I really like the SS Systems version and wanted to experience it with all the RenEx improvements. It didn’t disappoint; along with the pulldown, it really does change forever what you think a true compound exercise can be. After lunch we would be going through several static exercises so we cut the dynamic work there.

Throughout both of these mini-workouts I was impressed by the instruction, which was economical enough not to interfere with a subject’s concentration and mixed coaxing and criticism (always leavened with encouragement) with practical analogies and pinpointed direction. I’m not sure where some get the impression that RenEx involves nothing but rote commands.

Right before lunch we met with Jeff to discuss business systems. Spending an hour with Jeff, just based on energy level and intensity alone, you understand why Overload has been able to build the business they have. I won’t go into the details of what we discussed because I don’t believe they intend to give this material away. I will tell you it was incredibly useful information that we are already beginning to implement in our own business and that we will be seeking further consultation from Jeff in the months going forward. If you are a facility owner and decide to visit, don’t pass up the chance to meet with Jeff.

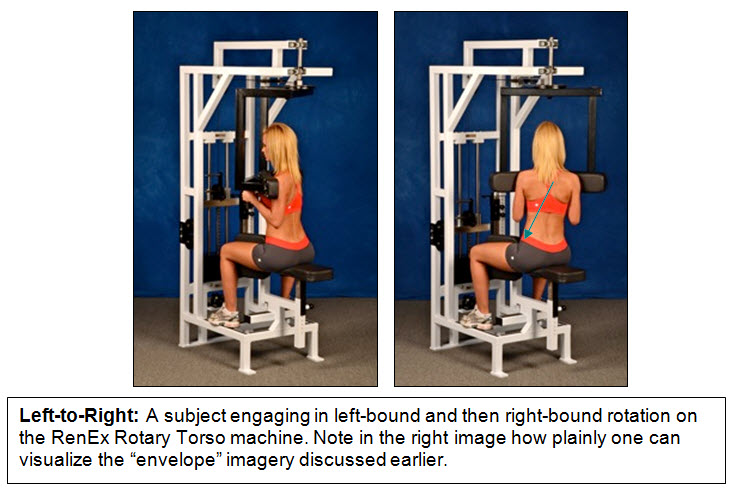

After lunch I was put back on the leg press to do a static set with feedback. Having already done a set of leg press to failure dynamically, it was brutal. This was followed by pullover and pulldown on the iPOPD – the most pure pre-exhaust I have ever experienced. But I should point out that with all three of these exercises there was the distinct sense that I had a lot to learn and was only scratching the surface of how to really engage each machine and get the most out of it. What is exhilarating though, is knowing that you can chase these performance improvements, tracking your proficiency as the line you produce exhibits less and less polarity. And I have no doubt that if you master a TSC exercise with feedback to guide you it will be transferable to a large degree to both blind TSC applications and dynamic exercise. There has just never been a tool like this to improve the quality of your muscular contractions.

I finished with a TSC overhead press, which uses an LCD readout rather than a graphical interface. I don’t know why, but I agree with Josh and Al that on this machine that interface feels right. Perhaps because I’m somewhat used to what a SS Systems overhead press feels like, I felt I performed at least marginally better. Having slowly graduated to and then sustaining what I think I remember being 60 pounds of force, I eventually began to fatigue and watched the numbers flicker downward. By the time Al was counting down the final ten seconds my arms were shaking with fatigue as I struggled to maintain between 1.5 and 2 pounds of force. While I long ago internalized the divergence of force and effort while inroading, it was still an extraordinary event to watch it happen numerically. For those of us who instruct others – often struggling to get subjects to really understand the real objective of exercise – feedback like this could be the ultimate tool. Rather than weeks of frustrating misunderstanding, a couple sessions with feedback may be like flipping a switch in their head.

The last actual strenuous work of the day was when Roxanne did a set of bicep exercise on the iPOPD. She was blown away by the intense and direct nature of the stimulus, with none of the joint aggravation, grip issues or accidental shoulder involvement of so many arm curl set-ups. She told me later that while pressing her wrists into the bottom pads she immediately thought of our older, frailer clients. This would allow them to reach a level of intensity unheard of with all the rate-limiting factors found on other machines. (My wife works in advertising, and the agency works on senior care community clients, so talk of exercise for the elderly is a big part of their business. While describing her experience on the iPOPD to a co-worker, keeping in mind she never knew the name of RenEx’s last conference, she said “you don’t understand, this is the f-ing future of exercise!”)

After that, Al took me through the features of the iMulti so I could get a feel for all of its various exercises without actually doing any real work. It is a pretty ingenious set-up that, on top of the TSC compound row, allows for a whole series of exercises for delicate structures and/or rehab work.

That sums up the highlights of our visit, but the day included a lot more than I have described, with Josh, Al and Jeff being extremely generous with their time and expertise. Both Al and Josh gave me advice on how to get the most out of my current equipment and this led to a discussion of what single static machine would compliment my studio best. We settled on the iPOPD, which is currently in production. This was the machine I originally had my eye on and being able to try it really sealed the deal. From the pelvic-tilt “get-set” to those last moments of muscular failure, the iPOPD just locks you into this feeling of pure muscular engagement. Once it arrives, I intend to switch all my clients over to it exclusively for the four exercises you can perform with it. The goal will be to use it to teach proper behavior that will be transferable to other machines, but it will also represent the majority of upper-body work done by my clients (other than chest press) for an extended period. I’m confident that with feedback, TSC will be all that is required for muscular development that could easily rival what average dynamic machines can offer. And while this will be far from a controlled study, it will be fun to test that assumption and I’m considering documenting my client’s experience with TSC at thestrongworks.com, so check-in over there in a few months if you are interested.

When I decided to visit Overload to experience RenEx, I’ll admit I didn’t do it as a raging skeptic. Having experienced the massive qualitative difference between generic gym equipment vs. say, Nautilus or Med-Ex or SS Systems machines, I could easily imagine that RenEx would be a hell of a lot better and be better at getting out of the user’s way. But really experiencing the machines and protocol makes all the difference, even at the superficial, initial consult level – it is that qualitatively different. Otherwise I wouldn’t be making what, for my operation, represents a considerable investment, with plans to invest further in the future. Client education is the key to client retention, in my opinion, and RenEx is simply the best teaching tool I’ve encountered.

There are a million ways to productively exercise, but what I want to offer my clients (and perform myself) is the safest and most efficient form that can be scaled to anyone and done for a lifetime. In that department, I’ve long assumed RenEx was the best choice. Much like what Ken’s writing did for my understanding of the objective of exercise, finally experiencing RenEx machines and protocol took away the assumed and made it real.

———————————————————————————————–

P.S. If you have not yet purchased your copy of The Future of Exercise now is your chance! Click Here to grab your copy today.

P.P.S. If you are interested in a private day of consulting and to experience first hand the RenEx Equipment feel free to contact us at info@ren-ex.com and put ‘On Site Audit‘ in the subject line. Days are limited and we only meet with serious exercise specialists. First come first serve!